"Clausewitz.... reminds us that the more rationalist we become, in other words, the more we forget perceptible reality and history, the faster and more violently reality and history are brought back to mind."

René Girard, "Clausewitz and Hegel" in Battling to the End: Conversations with Benoît Chantre, trans. Mary Baker (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2010), p. 37.

The colonial period of U.S. history contains a variety of interesting lessons. One of these pertains to the concept of a "virtuoso." The virtuoso was primarily characterized by curiosity. Rather than being overly specialized, the virtuoso explored a wide range of interests. The study of nature, art, literature, and theology all would have been pursuits common to this stereotype. This blog aspires to take this early category and use it as a point of departure for exploration and reflection.

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

René Girard on Consciousness

"It is obvious that, for there to be recognition, the master, who makes me exist simply by looking at me, must not be killed! Human consciousness is not acquired through reason, but through desire."

René Girard, "Clausewitz and Hegel" in Battling to the End: Conversations with Benoît Chantre, trans. Mary Baker (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2010), p. 31.

René Girard, "Clausewitz and Hegel" in Battling to the End: Conversations with Benoît Chantre, trans. Mary Baker (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2010), p. 31.

Monday, April 24, 2017

Foucault on Events

"An event is neither substance, nor accident, nor quality, nor process; events are not corporeal. And yet, an event is certainly not immaterial; it takes effect, becomes effect, always on the level of materiality.... Let us say that the philosophy of event shoudl advance in the direction, at first sight paradoxical, of an incorporeal materialism."

Michel Foucault, "The Discourse on Language"

Michel Foucault, "The Discourse on Language"

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

Girard on the Antichrist

"The other totalitarianism does not openly oppose Christianity but outflanks it on its left wing. [...] The most powerful anti-Christian movement is the one that takes over and 'radicalizes' the concern for victims in order to paganize it. The powers and principalities want to be 'revolutionary' now, and they reproach Christianity for not defending victims with enough ardor. In Christian history they see nothing but persecutions, acts of oppression, inquisitions. [...] The New Testament evokes this process in the language of the Antichrist."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 180-181.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 180-181.

Girard on Intelluctual's Adoration of Paganism

"Since the Renaissance, paganism has enjoyed among our intellectuals a reputation for transparency, sanity, and health that nothing can shake. Paganism is favorably perceived as always opposes to everything 'unhealthy' that Judaism and Christianity impose. [...] The intellectuals and other cultural elites have promoted Christianity to the role of number one scapegoat."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 179.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 179.

The Parodox of Christianity's Retreat in Girard

"This disintegration entails the retreat of religion almost everywhere, and this includes, paradoxically, the retreat of Christianity itself because 'sacrificial' vestiges from the past have contaminated it for such a long time that it remains vulnerable to the attacks of numerous enemies."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 179.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 179.

Girard on PostChristendom

"The majestic inauguration of the 'post-Christian era' is a joke. We are living through a carcatural 'ultra-Christianity' that tries to escape from the Judeo-Christian orbit by 'radicalizing' the concern for victims in an anti-Christian manner."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 179.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 179.

Girard and Modernity's Absolute

"The rise of 'victim power' coincides, not at all by accident, with the arrival of the first planetary culture. [...] I connect it with modern to underline the paradox of a value whose recent historical arrival in no way prevents it from asserting itself as the immutable and eternal. There were those who told us not long ago that human life existed in an absolute void of meaning. True enough, the old absolutes have collapsed - humanism, rationalism, revolution, science itself. And yet even today this absolute void does not prevail. There is the concern for victims, and it is that value, for better or worse, that dominates the total planetary culture in which we live. The world becoming one culture is the fruit of this concern and not the reverse."

"This new stage of culture has come about due neither to scientific progress nor to the market economy nor to the 'history of metaphysics.' [concern for victims] has directed the evolution of our world behind the scenes. If the concern for victims has fully appeared, it is because all the great expressions of modern thought are exhausted and discredited. After all the ideological collapses, our intellectuals believed they could settle down into the easy life of a nihilism without obligations or sanctions. But our nihilism is a pseudo-nihilism."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 177-178.

"This new stage of culture has come about due neither to scientific progress nor to the market economy nor to the 'history of metaphysics.' [concern for victims] has directed the evolution of our world behind the scenes. If the concern for victims has fully appeared, it is because all the great expressions of modern thought are exhausted and discredited. After all the ideological collapses, our intellectuals believed they could settle down into the easy life of a nihilism without obligations or sanctions. But our nihilism is a pseudo-nihilism."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 177-178.

Girard on the Modern Absolute

"Since the concern for victims becomes widespread only in the modern world, we might think that it would marginalize us in relation to the past, but this is not so. It is the concern for victims that marginalizes the past. We hear repeated in every way that we no longer have an absolute. But the inability of Nietzsche and Hitler to demolish the concern for victims and then later the embarrassed silence of the latter day Nietzscheans show for sure that this concern is not relative. It is our absolute."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 177.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 177.

Girard on Hitlerism and Nihilism

"In spite of its victims without number, Hitler's murderous enterprise ended in failure. It has had a twofold effect: it has accelerated the concern for victims, but it has also demoralized it. Hitlerism avenges its failure by making the concern for victims hysterical, turning it into a kind of caricature. yet in a world where relativism has seemingly defeated religion and every 'value' that is religious in origin, the concern for victims is more alive than ever. [...] but a dark pessimism took over the second half of the twentieth century. Although understandable, this reaction is as excessive as the arrogance preceding it."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 176.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 176.

Girard on the Pardox of Christianity's Advance and Decline

"Christian truth has been making an unrelenting historical advance in our world. Paradoxically, it goes hand in hand with the apparent decline of Christianity. The more Christianity besieges our world, in the sense that it besieged Nietzsche before his collapse, the more difficult it becomes to escape it by means of innocuous painkillers and tranquilizers such as the 'humanistic' compromises of our dear old positivist predecessors."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 174.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 174.

Girard on Knowledge as Social Transformation

"The most effective power of transformation is not revolutionary violence but the modern concern for victims. [...] it is the knowledge that separates the ritual meaning of the expression 'scapegoat' from its modern meaning. it deepens continually, and soon the mimetic reading of the structure of persecution will become more and more widespread. [...] Each time a new frontier is crossed, those whose interests are damaged oppose this change intensely."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 168.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 168.

Girard on the Effect of the Modern Victim Concept

"The cultures that were still autonomous cultivated all sorts of solidarity - familial, tribal, and national - but they did not recognize the victim as such, the anonymous and unknown victim, in the sense in which we say 'the unknown soldier.' Prior to this discovery there was no humanity in the full sense except within a fixed territory. Today all these local, regional, and national identities are disappearing: 'Ecco homo.' The essential thing in what goes now as human rights is an indirect acknowledgment of the fact that every individual or every group can become the 'scapegoat' of their own community. Placing emphasis on human rights amounts to a formerly unthinkable effort to control uncontrollable processes of mimetic snowballing."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 167-168.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 167-168.

Girard on Victimization in the Modern World

"The victims most interesting to us are always those who allow us to condemn our neighbors. And our neighbors do the same... In our world, in short, where we are all bombarding each other with victims... From now on we have our antisacrificial rituals of victimization, and they unfold in an order as unchangeable as properly religious rituals. First of all we lament the victims we admit to making or allowing to be made. Then we lament the hypocrisy of our lamentation, and finally we lament Christianity, the indispensable scapegoat, for there is no ritual without a victim, and in our day Christianity is always it, the scapegoat of last resort. As part of this last stage of the ritual, we affirm, in a nobly suffering tone, that Christianity has done nothing to 'resolve the problem of violence.'"

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 164.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 164.

Girard on Modern Pyschology

"this insight regarding scapegoats and scapegoating is a real superiority of our society over all previous societies, but like all progress in knowledge it also offers occasions to make evil worse. [...] Scapegoating phenomenon cannot survive in many instances except by becoming more subtle, by resorting to more and more complex casuistry in order to elude the self-criticism that follows scapegoaters like their shadow. [...] In a world deprived of sacrificial safeguards, mimetic rivalries are often physically less violent, but they insinuate themselves into the most intimate relationships... they become relationships of doubles, of enemy twins. This text enables us to identify the true origin of modern 'psychology.' [...] yes, we have changed a little since the time of archaic rituals but less than we would like to believe."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 159-160.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 159-160.

Girard on the Legacy of Christianity

"The modern understanding of 'scapegoats' is simply part and parcel of the continually expanding knowledge of the mimetic contagion that governs events of victimization. The Gospels and the entire Bible nourished our ancestors for so long that our heritage enables us to comprehend these phenomenon and condemn them."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 155.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 155.

Girard on the Mimetic Circle and Modernity

"Mythical-ritual societies are prisoners of a mimetic circle that they cannot escape since they are unable to identify it. This continues to be true today: all our ideas about humankind, all our philosophies, all our social sciences, all our psychological theories, etc. are fundamentally pagan because they are based on a blindness to the circularity of mimetic conflict and contagion. [...] To be a 'child of the devil' in the sense of the Gospel of John, as we have seen, is to be locked into a deceptive system of mimetic contagion that can only lead into systems of myth and ritual. Or, in our time, it leads into those more recent forms of idolatry, such as ideology or the cult of science."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 149-151.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 149-151.

Sunday, April 9, 2017

Palm Sunday - Reconstructing Triumph

Matthew 21:1-11

“When they had come near

Jerusalem and had reached Bethphage, at the Mount of Olives, Jesus sent two

disciples, 2 saying to them, “Go into the village ahead of you,

and immediately you will find a donkey tied, and a colt with her; untie them

and bring them to me. 3 If anyone says anything to you, just

say this, ‘The Lord needs them.’ And he will send them immediately.” 4 This

took place to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet, saying,

5 “Tell the daughter of Zion,

Look, your king is coming to you,

humble, and mounted on a donkey,

and on a colt, the foal of a donkey.”

Look, your king is coming to you,

humble, and mounted on a donkey,

and on a colt, the foal of a donkey.”

6 The disciples went and did as Jesus had directed them;

7 they brought the donkey and the colt, and put their cloaks on

them, and he sat on them. 8 A very large crowd spread their

cloaks on the road, and others cut branches from the trees and spread them on

the road. 9 The crowds that went ahead of him and that followed

were shouting,

“Hosanna to the

Son of David!

Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!

Hosanna in the highest heaven!”

Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!

Hosanna in the highest heaven!”

10 When he entered Jerusalem, the whole city was in

turmoil, asking, “Who is this?” 11 The crowds were saying,

“This is the prophet Jesus from Nazareth in Galilee.”

Sermon:

This past week I went onto Amazon and ordered a DVD miniseries from

the late 1970’s called, The Winds of War.

It was a short TV series created as an adaptation of a two-volume novel by the

same name. I saw the series for the first time a number of years ago with my

parents, but it had been on my mind a lot lately so I decided to order it. When

I tried to explain to my roommates why I had made such an unusual purchase, I

tried to sum it up by saying that the series could basically be described as a

“Jane Austin novel written by a dude who likes war stories.” One of my

roommates looked at me, blinked, and then said, “So, basically nothing like

Jane Austin.”

The point I would like to get to

though is a scene from the first volume of the series. Early on in the movie,

one of the protagonists, a Navy Commander who everyone calls “Pug” sets sail on

a German ship with his wife to head to a new posting as the Naval Attaché in

Nazi Germany. While on board, Pug becomes friendly with a German General who

ensures that they are able to dine at a better table. When it comes time to

toast Hitler, a British diplomat immediately sits down in a rather dramatic

display. This is soon followed by a discussion between the German General, the

British diplomat, and the U.S. Commander. One of the most fascinating parts of

the conversation, however, is a comments the German makes when he states, “You

made Hitler, you know, with your Versailles Treaty. Democracy, dictatorship,

monarchy, they’re all variations on the same theme – please the mob!” It’s a

catchy line precisely because there’s something to it. It is, obviously, far

too simplistic and yet most of us would probably agree that every form of

government has to please the mob. If you had to read Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in High School, it’s a

principle you would understand well.

The event described in today’s

scripture touches on this theme. It’s the beginning of a sequence of events

that spiral into Christ’s trial, execution, and resurrection. There is a

paradox, an intrinsic contradiction, in the event that we celebrate today. We,

the heirs of this story and this tradition, are privileged because we already

know the course of events and what their significance is. The crowd in this

story, however, is not aware of the paradox that they are enacting. We know

that they were celebrating the entry of someone they believed to be the new

King of the Jews – the Messiah who would liberate them from the clutches of

Roman imperial control. They understood the significance of the symbolism

inherent to this kind of entry – the donkey, the cloaks, the palm branches. For

nearly a hundred years they had been yearning for a leader who could lead a

military revolt, like the Maccabees, but many had tried and failed. Even some

of Jesus’ own disciples believed that this was the “Kingdom of Heaven” that

Jesus so often referred to.

So, when we read about this scene

where people line the streets and celebrate the entrance of their Messiah, we

are seeing something that is incredibly ironic. They are celebrating the

entrance of a man who they will crucify at the end of the week. They are not,

in fact, celebrating the coming Kingdom of God, but the kingdom that they

themselves hope to build. They are celebrating a nationalistic, militaristic, ethnocentric,

political vision of their own salvation. This is the paradox. The crowd is, in

fact, celebrating something that they don’t understand. In all likelihood, they

are celebrating something that they would likely abhor. And yet, they do so

because it fulfilled the words of the prophets who their ancestors killed and

whose fate Jesus is tied to at the end of today’s scripture when Matthew writes,

“This is the prophet Jesus from Nazareth in Galilee.” This is why Jesus calls

attention to the people’s hypocrisy only two chapters after today’s passage

when he states that:

“Woe to you,

scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you build the tombs of the prophets and

decorate the graves of the righteous, 30 and you say, ‘If we

had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them

in shedding the blood of the prophets.’ 31 Thus you testify

against yourselves that you are descendants of those who murdered the prophets.

32 Fill up, then, the measure of your ancestors. 33 You

snakes, you brood of vipers! How can you escape being sentenced to hell? 34 Therefore

I send you prophets, sages, and scribes, some of whom you will kill and

crucify, and some you will flog in your synagogues and pursue from town to

town, 35 so that upon you may come all the righteous blood shed

on earth, from the blood of righteous Abel to the blood of Zechariah son of

Barachiah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar. 36 Truly

I tell you, all this will come upon this generation.” (Matt. 23:29-36)

Jesus takes a moment here to teach us that

children often repeat “the crimes of their fathers precisely because they

[believe that they] are morally superior to them.”[1] When community’s

gather around a scapegoat to kill it, they are enacting a form of violence that

stands at the center of human origins. That is why Jesus refers to the murder

of Abel. Abel’s murder results in the first law and ritual that prohibits

murder. Most of us know this, but the part that we often forget is that Abel’s

murder also creates the first nation – a people set apart by a mark and a

crime.

When

the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote the Leviathan soon after the English Civil War he was not far off from

the Biblical account when he suggested that the origins of civilization rest in

“the war of all against all.” The crime of Cain is the crime of humanity. If we

look to the Ten Commandments, we will notice that the second half are directed

at one’s relationship to one’s neighbor.

You

shall not kill.

You

shall not commit adultery.

You

shall not steal.

You

shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

You shall not

covet the house of your neighbor. You shall not covet the wife of your

neighbor, nor his male or female slave, nor his ox or ass, nor anything that

belongs to him. (Exod. 20:17)

There’s a reason why this last commandment

is the longest and most explicit. It’s the most important, precisely because it

is our desires that generate all of those other sins. We are shaped by the

people around us. Their desires affect our desires and their possessions retain

a quality that we too often wish to possess. Rivalry exists at the heart of

human relations. This is even evident when we look at our own mythologies of

“keeping up with the Jones’” or the “American Dream.” There is something

fundamental to this and it feeds into the ways that crowds behave.

But

this is also where the Biblical witness is unique among all world religions. The

Judeo-Christian tradition is full of stories where the “turmoil” that we hear

about in verse 10 of today’s passage turns into a chaotic scene where the

crowds must release their anxiety in a violent assassination of a victim, which

the Bible calls a ‘scapegoat.’ Matthew ends today’s passage with a foreshadow

of what is to come precisely because it is a repetition of what we can find

throughout the stories that precede it. Crowds become frustrated by the

inhibition of their own desires and they find targets to kill as a result. John

the Baptist was beheaded because the daughter of his wife whipped a crowd up

into a frenzy with a dance. The Suffering Servant in Second-Isaiah dies at the

hands of a hysterical mob that lynches him. The Bible is, in fact, full of

stories about the collective lynching of a prophet and the revelation of God in

Jesus Christ is essentially the same.

And

this is precisely what makes Christianity unique. Christianity shines a light

upon this fundamental human tendency and exposes the crime for what it is.

Christianity asserts that the victims are, in fact, innocent. It is the first

religion to protect the weak, the vulnerable, and the marginalized. Almost all

world religions have a single victim at the source of their theology.

“[In] India: the

dismemberment of the primordial victim, Purusha, by a mob offering sacrifices

produces the caste system. [And] We find similar myths in Egypt, in China,

among the German peoples – everywhere.”[2]

Humanity has universally emerged out of

the idea that the body of a victim often germinates to produce new life. But

Christianity is unique in its protest. Why all the other world religions,

particularly paganism, highlight the efficacy of sacrifice Christianity points

out the sin at the heart of all of this. The victim is not demonized and then

transformed into something else. The victim, the marginalized person, who is

targeted by a community experiencing chaos is always held up as a descendent of

Abel.

Christianity

is unique because it says that God Himself, came to earth, to die and suffer at

the hands of a race enraptured with this practice of objectification and

scapegoating. And in the process God offered us something else in the person

and work of Jesus Christ. He offered us a different path – a path of peace and

illumination. When we look to a theology of the cross, what we really find is a

spotlight. The cross is a spotlight that shines onto each and every one of our

personal moments of triumphal entry. When we rise up to celebrate ourselves and

our own desires, the cross has the power – through the witness of the

Resurrection – to show us a reflection of ourselves. It has the power to make

us stare into the painting that killed Dorian Gray.

The

only way to celebrate Palm Sunday properly, is to look forward. We celebrate

the coming of a King who represents a Kingdom not our own. We celebrate the

coming of a King who offers us the opportunity to transform ourselves into

something far more beautiful. We celebrate a Messiah who offers us a salvation

far beyond what we could imagine for ourselves. When we wave our palms, and

sing our songs we do so from this side of history, a side that sees this moment

as the transformational event it really is. This is precisely why the German

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche hate Christianity. He recognized that is

intrinsically associated with democracy and holds an absolute concern for

victims. Judaism and Christianity are unique in this regard and this is

precisely where their power lies. Christ compels us to follow in His Way, which

through the power of the Holy Spirit, leads us towards a path that moves us

beyond our own narrow-minded shortcoming, and towards a vision of the world as

God sees it.

[1] Réne Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning,

trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 20.

[2] Réne Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning,

trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 82.

Saturday, April 8, 2017

Girard on the Paradox of Hostility Toward Religion

"The modern tendency to minimize religion could well be, paradoxically, the last remnant among us of religion itself in its archaic form, which seeks to keep the sacred at a safe distance. The trivialization of religion reflects a supreme effort to conceal what is at work in all human institutions, the religious avoidance of violence between members of the same community."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 93.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 93.

Thursday, April 6, 2017

Girard on the Woman Caught in Adultery

"Jesus transcends the Law, but in the Law's own sense and direction. He does this by appealing to the most humane aspect of the legal prescription, the aspect most foreign to the contagion of violence, which is the obligation of the two accusers to throw the first two stones. The Law deprives the accusers of a mimetic model."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 58-59.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), pp. 58-59.

Wednesday, April 5, 2017

Girard on Cyclical Violence

"The more one is crucified, the more one burns to participate in the crucifixion of someone more crucified than oneself."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 21.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 21.

René Girard on why we think we are superior to Peter

"The children repeat the crimes of their fathers precisely because they believe they are morally superior to them. This false difference is already the mimetic illusion of modern individualism, which represents the greatest resistance to the mimetic truth that is reenacted again and again in human relations. The paradox is that the resistance itself brings about the reenactment."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 20.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 20.

Monday, April 3, 2017

René Girard on the Disappearance of Real Differences

People "have ears only for the deceptive celebration of differences, which rages more than ever in our societies, not because real differences are increasing but because they are disappearing."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 13.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 13.

René Girard on the Paradox of Desire

"The more desperately we seek to worship ourselves and to be good 'individualists,' the more compelled we are to worship our rivals in a cult that turns to hatred."

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 11.

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, trans. James G. Williams (New York: Orbis, 2001), p. 11.

Saturday, April 1, 2017

Being in Plato's 'Sophist'

"Then since we are in perplexity, do you tell us plainly what you wish to designate when you say “being.” For it is clear that you have known this all along, whereas we formerly thought we knew, but are now perplexed. So first give us this information, that we may not think we understand what you say, when the exact opposite is the case."

Plato, Sophist, 244a.

Plato, Sophist, 244a.

Heidegger on the Relation of Being and Time

"[F]initude is not some property that is merely attached to us, but is our fundamental way of being."

Martin Heidegger, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995), p. 5.

Martin Heidegger, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995), p. 5.

Epicurus on Death

"So death, the most frightening of bad things, is nothing to us; since when we exist, death is not yet present, and when death is present, then we do not exist. Therefore, it is relevant neither to the living nor to the dead, since it does not affect the former, and the latter do not exist."

Epicurus, The Epicurus Reader, eds. B. Inwood & L.P. Gerson (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 1994), p. 29.

Epicurus, The Epicurus Reader, eds. B. Inwood & L.P. Gerson (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 1994), p. 29.

Montaigne on Death and Philosophy

"To philosophize is to Learn How to Die... study and contemplation draw our souls, somewhat outside ourselves, keeping them occupied away from the body, a state which both resembles death and which forms a kind of apprenticeship for it."

Michel de Montaigne, "To Philosophize is to learn How to Die" [1580] in The Essays: A Selection, ed. M.A. Screech (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993), p. 17.

Michel de Montaigne, "To Philosophize is to learn How to Die" [1580] in The Essays: A Selection, ed. M.A. Screech (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993), p. 17.

Monday, March 27, 2017

Merleau-Ponty on Perception, the Intentional Arc, and the Dialogue between Body and Mind

"For us the body is much more than an instrument or a means; it is our expression in the world, the visible form of our intentions." Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964), p. 5.

"The body is our general medium for having a world." Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. C. Smith (London: Routledge, 1962), p. 146.

"The body is our general medium for having a world." Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. C. Smith (London: Routledge, 1962), p. 146.

Sunday, March 26, 2017

Pious Wolves

Mark 12:38-44

As he taught, he said, “Beware of

the scribes, who like to walk around in long robes, and to be greeted with

respect in the marketplaces, 39 and to have the best seats in

the synagogues and places of honor at banquets! 40 They devour

widows’ houses and for the sake of appearance say long prayers. They will

receive the greater condemnation.”

41 He sat down opposite the treasury, and watched the crowd

putting money into the treasury. Many rich people put in large sums. 42 A

poor widow came and put in two small copper coins, which are worth a penny. 43 Then

he called his disciples and said to them, “Truly I tell you, this poor widow

has put in more than all those who are contributing to the treasury. 44 For

all of them have contributed out of their abundance; but she out of her poverty

has put in everything she had, all she had to live on.”

Sermon:

Through the course of Lent, we have

been coloring in the posters that you see around you. Today’s poster deals with

the topic of love and towards the bottom of it you can see the scripture that

was just read for us. Much of it is probably familiar, but sometimes it’s

helpful to hear familiar passages in their original contexts. Often times, the

setting of a passage can shed light upon its intent and meaning. This morning I

want to bring our attention to the last two section (slides) of today’s

scripture – the contrast of the pious religious figures who Jesus damns and the

widow who gave everything she had.

I suppose that I decided to preach on

these last two sections of today’s scripture because a classmate of mine (Andy

Gill) from seminary published an article on the Christian website Patheos entitled, “MegalomaniacticPastors: What if Your Pastor’s a Functional Psychopath?” The image at the top

of the article depicted a scene from the famous show House of Cards where Frank Underwood, President of the United

States and noted sociopath, skillfully manipulated a church’s congregation to

deflect blame away from his role in the death of someone’s child. Now, I

haven’t spent much time talking to the author of this article, even though we

went to seminary together, we never really crossed paths. As a result, Mike

might know him better than me. However, I do like to read what he publishes

online. His writing is insightful and usually quite pointed. I don’t always

agree with him, often times I feel like his perspective is shaped by a bit of a

chip on his shoulder that he must have acquired in his past experiences with

evangelical megachurch cultures, but I do find his writing to be useful reading

and this week it connected with the scriptures I was looking to preach on.

The whole point of my acquaintances

article wasn’t really new. Forbes and

many other journals have reported on the prevalence of sociopaths in religion

for many years now. They even have a ranking system for the occupations that

attract the most and least sociopaths, based upon psychological studies. [1]

Most:

1. CEO

2. Lawyer

3. Media

4. Sales

5. Surgeon

6. Journalist

7. Police

Officers

8. Clergy

9. Chef

10. Civil

Servants

Least:

1. Care

Aide

2. Nurse

3. Therapist

4. Craftsperson

5. Beautician/Stylist

6. Charity

Worker

7. Teacher

8. Creative

Artist

9. Doctor

10. Accountant

So,

my acquaintances argument wasn’t really a new concern, but it’s one we often

face when we turn on Christian television and see preachers asking for ‘seed

money’ that will make you rich or even the differences between one of the 20th

centuries greatest preachers, who was undoubtedly a sincere and authentic man

of genuine intentions, and a son who makes close to a million dollars a year

running ministries based out of North Carolina without many of the ethical boundaries

his father was sure to employ.

I think that there are genuine questions

we should have around many of the ‘Christian’ leaders and practices that we

have seen in this country. Jesus himself throws shade at these things! So, when

we see prosperity gospel preachers entice poor people out of the little they

already have, we should be appalled. Jesus told us that these people who use

appearances and earthly conceptions of holiness to manipulate others will in

the end face condemnation. They are wolves’ intent on devouring their flocks.

Likewise, when we see preachers preying on people’s fears or emotions, we

should wonder what they’re gaining from that. Are they, in a sense, holding the

people they’re baptizing under water for far longer than is necessary just

because it gives them that extra little bit of pleasure?

As someone who grew up around

Pentecostal and Southern Baptist churches, I’ve seen a lot of emotional

manipulation within the church. In some contexts, a pastor’s success can be

tied to how well he pulls at the emotions of the congregation, as though the

crowd was nothing more than a marionette in need of deft fingers capable of

synchronizing its movements with the choreography of a dance. The words,

movements, and lighting can be adjusted to create an experience – perhaps even

a high – before the people even arrive.

But this brings us to an important

question. What’s the difference between sociopathic manipulation and art? My

acquaintance ended his article with a quote from Donald Miller which said, “I think a lot of […] shame-based religious and political [methodologies

have] more to do with keeping people contained than with setting them free. And

I’m no fan of it.” Art, like religion, also elicits emotional responses

intentionally. It creates things in the tangible world to affect the worlds

inside of you, your neighbor, and me. When we go to a novel, a play, or a

movie, we are, in a sense, looking to be moved by the force of something –

we’re seeking a moment of change or reinforcement. But the question for art,

like religion, is intent. When an artist creates a work to confine, rather than

liberate, you we might call it propaganda.

Likewise, when

faith is used to confine, restrict, and exploit you we can justifiable call it

sociopathic. Religious sociopathy exists not just in the leaders who seek extraordinary

amounts of recognition, honor, and financial gain, but also in institutions

that care more about building empires than healthy lives. When a church

community loses sight of the larger picture of how faith fits into the whole

human experience, it loses a central element intrinsic to the power of the

Gospel. Faith touches all aspects of our humanity – our emotions, our

intellect, our spirits, and our social lives. When we lose sight of helping

each other grow on all of these fronts, we fail to truly exhibit the love of

God – which is what we are called to live into. Our lives should be shaped by a

love that affects every aspect of our humanity. If we can do that, then we too

can be like the widow who gave everything. Our submission to the movement of

the Spirit, which elicits love in everything it touches, is what empowers and

saves us.

[1]

https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyclay/2013/01/05/the-top-10-jobs-that-attract-psychopaths/#1424f81d4d80

Friday, March 24, 2017

Abraham Kuyper Prize for Public Theology

Thus far, I haven't weighed in on Princeton Seminary's decision to abstain from awarding the Abraham Kuyper Prize for Public Theology to Tim Keller, Pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church. However, I would like to be very clear. I support the seminary's decision to rescind it's decision to award the Prize to Keller, yet retain it's invitation for him to speak. I have no issues with inviting like Keller to Princeton to speak. He is, after all, a very successful pastor.

However, I do think that it is appalling that the Abraham Kuyper Center for Public Theology decided to award him with a cash prize and formal honor without carefully considering the message they were sending. As Mainline Protestants, we can respect our conservative brothers and sisters as fellow Christians, but we should never give the impression that we endorse their bigotry, racism, homophobia, or other exclusionary ideologies.

I signed the petition to reverse the decision to award the Kuyper Prize to Tim Keller precisely because I do not want my alma mater to be associated with those things. We already live in a society where the Gospel is seen as an oppressive force intent on repression and exclusion, where white heteronormative narratives even define common conceptions of soteriology, we don't need to reinforce those perceptions and blur the lines between those who endorse those views and those who do not. Dechristianization will deliver it's blow to American Evangelicalism in good time, that process has already begun, and there's no need to fight evangelicals or conservatives. Such a tactic is fruitless.

However, progressive Christians should retain their distinct identity because it is that identity that can survive the progress of dechristianization. A postchristian America is not going to turn towards Tim Keller's message. It will, instead, turn towards a far more robust post-Christendom faith of inclusiveness. Refusing to endorse Keller is important precisely because it is his Christendom that must fall in order for the Gospel to be reborn.

I support my female colleagues and I support the LGBTQ community and I do not believe that Princeton should endorse those who seek to silence and oppress them.

Merleau-Ponty on What it Means to be Human

"Merleau-Ponty sees the body and perception as the seat of personhood, or subjectivity. At root, a human being, is a perceiving and experiencing organism, intimately inhabiting and immediately responding to her environment."

Havi Carel, Illness: The Cry of the Flesh, revised edition (Durham, UK: Acumen, 2013), pp. 24-25.

Havi Carel, Illness: The Cry of the Flesh, revised edition (Durham, UK: Acumen, 2013), pp. 24-25.

Fromm on Social Pathologies

“The fact that millions of people share the same vices does not make

these vices virtues, the fact that they share so many errors does not

make the errors to be truths, and the fact that millions of people share

the same form of mental pathology does not make these people sane.”

― Erich Fromm, The Sane Society, 1955

― Erich Fromm, The Sane Society, 1955

Monday, March 20, 2017

Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night

A Poem by Dylan Thomas:

"Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light."

"Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light."

Poetry

"The future of poetry is immense, because in poetry, where it is worthy of its high destinies, our race, as time goes on, will find an ever surer and surer stay." Matthew Arnold, "The Study of Poetry" Essays in Criticism, 1889.

Monday, February 20, 2017

Love: A Sermon from Feb 19th 2017

Song of Solomon 8:6-7

“Set me as a seal

upon your heart,

as a seal upon your arm;

for love is strong as death,

passion fierce as the grave.

Its flashes are flashes of fire,

a raging flame.

7 Many waters cannot quench love,

neither can floods drown it.

If one offered for love

all the wealth of one’s house,

it would be utterly scorned.”

as a seal upon your arm;

for love is strong as death,

passion fierce as the grave.

Its flashes are flashes of fire,

a raging flame.

7 Many waters cannot quench love,

neither can floods drown it.

If one offered for love

all the wealth of one’s house,

it would be utterly scorned.”

Sermon:

Some of you may not know this, but one

of Dorothy’s jobs is to sit and listen to the random and often crazy ideas of

her boss. For quite some time now, I’ve been going on about how I’ve been

wanting to teach on Song of Solomon. And as you might expect, she’ll sit there

and nod her head and give that look that says, “Sure, I understand. But are you

sure that’s a good idea?” When that happens, I usually imagine myself standing

there then laugh and walk back in my office wondering if I should really do

something so foolish. After all, there’s a reason most preachers stay clear of

this book.

But I suppose that my interest in

teaching this book comes from two sources. First, no one ever touches on it.

For me, that’s a fun challenge to be surmounted. There’s something exhilarating

about doing something different and perhaps even a bit scandalous. Second, I

picked up a commentary last year that has had me pretty jazzed. It’s entitled, Exquisite Desire: Religion, the Erotic, and

the Song of Songs and it’s written by Carey Ellen Walsh. If you ever come

to my office I can show it to you, and the first thing you’ll notice is that

the cover is well suited to the content of the book it studies. The cover illustrates the genre of it's subject - religious erotica.

The tipping point in my resistance to

touching on this book of the Bible finally came this week with the celebration

of Valentine’s Day. When I came to the office on Tuesday I had to come up with

a sermon topic so it made sense for me to preach about love. I’ve preached on

love before, of course, but never romantic erotic love. As most of you know,

the Greek New Testament has a number of words for love and each carries a

different connotation. Greek, unlike English, distinguishes between different

types of love. Many of us are probably familiar with the term agape which refers to the kind of love

that God or a parent may have for us. Nearby we have a city with a Greek name –

Philadelphia is drawn from phileo

which is the kind of love one might have towards their close friends, think

David and Jonathan. But there is, of

course, another type of love, namely eros.

So today I want us to think through this kind of love.

In a moment, Marie is going to

start a clip that might help us think through this topic. Some of you may not

be very familiar with some of the references, but I think you will get the

overall message anyway. I think that there’s a central lesson to be learned.

Our society, or perhaps even most

societies, is in a constant state of flux over the question of what love really

means. We don’t really know how to answer the question definitively. It’s a bit

of a mystery really, and yet I think there are some things we can know. First

and foremost, there are always mythologies that play into our concepts of love.

We have the fairy tales where a noble knight rides in in chivalric prose to

save the fair maiden from some sort of evil. We have the idea of soul mates –

the idea that there was one specific person God created for you to marry. We

have the mythology that couples are supposed to feel the same feelings they

felt on their wedding day 40 years later, as though no one ever feels the

seven-year itch or that ‘happily ever after’ somehow comes easily.

In some ways, the Song of Solomon is

like these things. It’s a poem that “portrays erotic love between two young

people who are not yet betrothed and whose union is not yet recognized by the

young woman’s family.”[1]

Pastors aren’t normally drawn to preach on texts that hint strongly at

premarital hanky-panky. But maybe there’s a lesson in our history with this

book. Christians have an interpretative tradition that’s nearly two thousand

years old now, wherein we read this book of the Bible allegorically. In other

words, we have often realized that we can’t really fit this book of the Bible

together easily with our traditional views about what a young couple should be

up to before they get married.[2]

So, we’ve decided to read a rather long poem, unsurprisingly, in a rather

poetic way. We’ve said that this poetry foreshadows the love Christ has for His

Church – that it’s true purpose is to highlight the final union the two will

have when Christ finally returns. This approach harkens back to the famous

phrase Paul gave us when he said, “Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ

loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Ephesians 5:25).

I think there’s truth to this point. I

believe that it is an edifying and hopeful lens we can take towards our future.

However, I also think that it obscures the value that the Song of Solomon might

have in itself, some intrinsic worth that it might have apart from our attempts

to explain it away through the words of Paul or other Biblical writers. The

video we just watched talked a lot about how the old chivalrous ideas of love

are falling away in the age of online dating – how ‘excarnation’ is eroding the

concepts of love we developed in the late middle ages.

When

I was much younger it was easy to point out the flaws of the fairy tale love

popularized by Disney movies, but maybe there is a value in the fairy tale even

if it’s not true. Maybe it was never intended to tell the truth we find in

history or science. Perhaps it’s possible that the Song of Solomon was never

intended to serve as an ethical treatise for how we should go about dating,

marrying, or instructing our children. Poetry isn’t usually intended for those

purposes, is it? We don’t go to the Psalms to learn how we should treat others.

If we did, we’d all probably be quite violent! No, we go to the Psalms and Song

of Solomon because they both speak to something in us that is definitively

human – they speak to our souls.

I

think that it is possible that in a day and age when we’re experiencing massive

levels of objectification and ‘excarnation’ we might need the fairy tales to

remind us of the ideals we should strive for. One of my favorite philosophers

is the Swiss-born Alain

de Botton. In his novel The

Course of Love, he writes about our shallow understanding of real-life intimacy: "What

we typically call love is only the start of love."[3]

And yet this is one of the cruelest games we play on young couples. We suggest

that this transitory high is supposed to last, as though it will never change

with time, experience, and strong personalities. It’s as though we don’t want

to tell them that they’re going to be tested. It’s as though we don’t want to

let them in on the secret that they’re going to have to work hard later on.

Sometimes, I wonder if it’s as though no one wants to spoil the surprise.

For most of the people in this

room, this was the big challenge. Most of us have had to face the crumbling façade

of expectations that we thought we knew, only to be challenged to rise up to

the occasion of trying to figure out what love means beyond the fairy tales,

beyond the myths, and beyond the images of our youth. On the other hand, those

of us who are a bit younger are facing a completely different monster. I, like

most of the millennials here, have live not only at the tail end of the chivalric

period we all share but also the beginning of the new era that we just learned

about in that video. Our society has moved away from the dreamy land of shiny

knights and fair maidens and landed in a world where we draft lists of what we

want in a partner. As the video pointed out, these lists can often reflect an

element of our own narcissism. Or, if we set aside our dreams, we shut

ourselves off emotionally and go through the dating process trying to stimulate

ourselves without becoming emotionally vulnerable. I think that it’s fair to

say that we haven’t really made any progress. We’ve just added a bit of

sophistication to our chaos.

This is why I wish more people told us about a

deeper kind love, the long-term kind. The one forged by compromise, patience

and accepting other people as they are, not as we wish them to be. I’m

particularly drawn to the words of Paul, where he says,

“Love

is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or

rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it

does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. It

bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love

never ends.” (1 Cor. 13:4-8)

This is why the canon is so important. As Christians, we

read our texts in the context of the whole Bible. If we stuck to the words of

Song of Solomon alone, we probably wouldn’t have much of an ethical outlook on

how we can erotically love someone ethically. We’d have some really explicit

erotic literature, but we wouldn’t have a larger context to place it into.

More than

anything else, love is an act. It’s something we choose to do. Up behind me

there are four quotes, one of these is from the French Existentialist Albert

Camus. As you can see it reads, “What does love add to desire? An inestimable

thing: friendship.”[4] I think this is, perhaps,

the most essential lesson. It’s easy to figure out that the two most important

things for a marriage are kindness and empathy.[5]

This is true not just for romance, but for all relationships. Love isn’t just

about chemistry. Chemistry is a great start, but it’s not the most essential

part. Love is about building something beautiful.

This may

be a but abstract, but I think it’s pretty essential. Beauty and love are

intricately connected and I’m not just referring to how good looking the person

next to you might be. No, I’m talking about what you can build with the person

next to you, your spouse, your friends, your children. There’s a reason the

Bible often refers to the beauty of Creation when everything is going well and its

ugliness when God’s mad at what we’ve been doing. There’s an inherent value in

what we can build together. That’s why we gather here together in this place,

or with our families, or with our friends. We’re trying to live into the

possibility of building something beautiful to live within both in the present

and in the future.

I don’t

want to get into Plato too much this morning, although I’m sure that you all

know that I’m tempted, but I think this is important. Why would the creator of

the universe create our world at all? He certainly doesn’t need us. Perhaps the

answer is the same as the answer any artist would give. Beauty is always

valuable, particular when it’s present in relationships – be they romantic,

fraternal, familial, or even church-based. As one author, I read this week

wrote:

“Beauty either of an

individual, or indeed of anything else we value as supremely beautiful, is the

creative environment in which we try to secure some share of whatever we deem

to be of value for ourselves.”[6]

All of us here together, that’s

beautiful. It’s valuable. When we build something together with our partners

that too is beautiful – it has inherent value. It’s made stronger by the

guidelines and teachings that we can find through the Bible.

But I think it’s important to remember that beauty isn’t

just about ethics. It’s not just about our lists of what to do and what not to

do. Beauty can be the thing that drives our efforts to do the right thing. The

act of creating can push us in the right direction. So perhaps it makes sense

that we get the Song of Solomon before we ever get Paul. Maybe we’re human

before we’re ever civilized. Maybe we need fairy tales to guide us through the

long lonely nights and push us towards the kinds of acts that make us a better

species. Maybe we need a weird little book smack-dab in the middle of the Bible

to remind us that the ideals and naivety behind a little hanky-panky might

actually be what makes us truly beautiful. Should that be guided by wisdom and

experience? Of course, but maybe there’s a little wisdom in the Song of Solomon

after all – a testament to the ideals towards the passions that should drive us

all to make the world just a little more beautiful. After all, I’m pretty

convinced that God is in the business of transforming broken things into things

of wonder. May we all strive to live and love into the example Christ gave us –

to be moved to build and create relationships of beauty. Amen.

[1] Michael V. Fox,

“Introduction to The Song of Solomon” in NRSV Study Bible.

[2] Many of these traditional views

aren’t actually drawn from strong Jewish sources, but Stoic ones that began to

influence the Ancient Near East roughly 200 years before Christ, culminating

around 200-300 AD. This was, in a sense, a sexual revolution. See: Michel

Foucault, The Care of Self: Volume 3 of

The History of Sexuality, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books,

1988).

[3] Alain de Botton, The Course of Love (New York: Simon

& Schuster, 2016), p. 8.

[4] Albert Camus, Carnets III (1951-1959).

[5] Emily Esfahani Smith, “Masters of

Love: Science says lasting relationships come down to – you guessed it –

kindness and generosity” in The Atlantic,

June 12, 2014; and Jake Newfield, “Why Empathy Is Key for Your Relationships”, The Huffington Post, November 20th

2015.

[6] Frisbee Sheffield, “Why There Is No Such Thing as a Soul Mate: Reading

Plato on Valentine’s Day”: http://www.thecritique.com/articles/there-is-no-such-thing-as-a-soul-mate/?utm_content=buffer1d699&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com&utm_campaign=buffer

Friday, February 17, 2017

Philosophy and Tyrants

"The philosopher's every attempt at directly influencing the tyrant is necessarily ineffectual."

Alexandre Kojève, Tyranny and Wisdom in Victor Gourevitch and Michael Roth, eds., Leo Strauss, On Tyranny: Including the Strauss-Kojève Debate (New York: Free Press, 1991), pp. 165-166.

Alexandre Kojève, Tyranny and Wisdom in Victor Gourevitch and Michael Roth, eds., Leo Strauss, On Tyranny: Including the Strauss-Kojève Debate (New York: Free Press, 1991), pp. 165-166.

Saturday, January 28, 2017

Proud Pastor

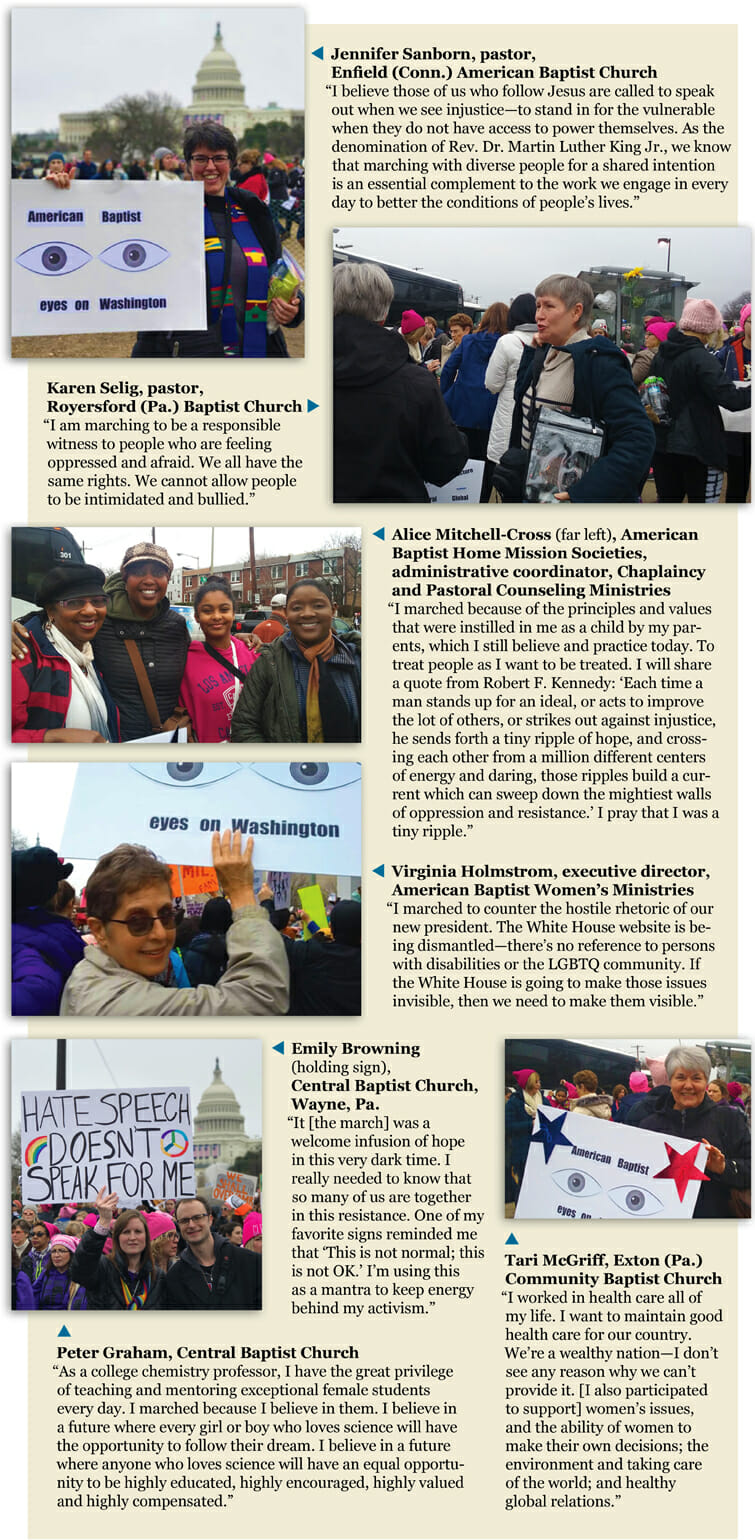

I couldn't be prouder of my congregants. A week ago my ladies boarded a

bus at our denomination's headquarters in Valley Forge and rode down to

Washington D.C. to join the protest. Two of them are featured in this

American Baptist Home Mission Societies article:

Saturday, January 7, 2017

The Hegemony of Pop Culture

"They live in the unreal realm of the mega-rich, yet they hide behind a folksy facade, wolfing down pizza at the Oscars and cheering sports teams from V.I.P. boxes... Opera, dance, poetry, and the literary novel are still called 'elitist', despite the fact that the world's real power has little use for them. The old hierarchy of high and low culture has become a sham: pop is the ruling party."

Alex Ross, "The Naysayers: Walter Benjamin, Theodore Adorno, and the Critique of Pop Culture", The New Yorker, September 15th 2014.

Alex Ross, "The Naysayers: Walter Benjamin, Theodore Adorno, and the Critique of Pop Culture", The New Yorker, September 15th 2014.

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

Adorno on Truth and Suffering

"The need to let suffering speak is a condition of all truth. For suffering is objectivity that weighs upon the subject."

Theodore Adorno, Negative Dialectics (Routledge, 2003), p. 17.

Theodore Adorno, Negative Dialectics (Routledge, 2003), p. 17.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)